Lassa Virus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Lassa mammarenavirus'' (LASV) is an

Lassa viruses are enveloped, single-stranded, bisegmented,

Lassa viruses are enveloped, single-stranded, bisegmented,

''Lassa mammarenavirus'' gains entry into the host cell by means of the cell-surface receptor the alpha-dystroglycan (alpha-DG), a versatile receptor for proteins of the

''Lassa mammarenavirus'' gains entry into the host cell by means of the cell-surface receptor the alpha-dystroglycan (alpha-DG), a versatile receptor for proteins of the

The life cycle of ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is similar to the Old World arenaviruses. ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' enters the cell by the

The life cycle of ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is similar to the Old World arenaviruses. ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' enters the cell by the

arenavirus

An arenavirus is a bisegmented ambisense RNA virus that is a member of the family ''Arenaviridae''. These viruses infect rodents and occasionally humans. A class of novel, highly divergent arenaviruses, properly known as reptarenaviruses, have ...

that causes Lassa hemorrhagic fever,

a type of viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families '' Filoviridae'', ''Flav ...

(VHF), in humans and other primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

s. ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is an emerging virus and a select agent

Under United States law, Biological select agents or toxins (BSATs) — or simply select agents for short — are bio-agents which (since 1997) have been declared by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) or by the U.S. Departme ...

, requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment. It is endemic in West African countries, especially Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

, the Republic of Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

, and Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

, where the annual incidence of infection is between 300,000 and 500,000 cases, resulting in 5,000 deaths per year.

As of 2012 discoveries within the Mano River

The Mano River is a river in West Africa. It originates in the Guinea Highlands in Liberia and forms part of the Liberia-Sierra Leone Liberia–Sierra Leone border, border.

The districts through which the river flows include the Parrot's Beak ...

region of west Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

have expanded the endemic zone between the two known Lassa endemic regions, indicating that LASV is more widely distributed throughout the tropical wooded savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

ecozone in west Africa. There are no approved vaccines against Lassa fever for use in humans.

Discovery

In 1969, missionary nurse Laura Wine fell ill with a mysterious disease she contracted from an obstetrical patient in Lassa, a village inBorno State

Borno State is a state in the North-East geopolitical zone of Nigeria, bordered by Yobe to the west, Gombe to the southwest, and Adamawa to the south while its eastern border forms part of the national border with Cameroon, its northern border ...

, Nigeria. She was then transported to Jos, where she died. Subsequently, two others became infected, one of whom was fifty-two-year-old nurse Lily Pinneo who had cared for Laura Wine. Samples from Pinneo were sent to Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

in New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

where a new virus, that would later be known as ''Lassa mammarenavirus'', was isolated for the first time by Jordi Casals

Jordi Casals i Ariet (born 15 May 1911, Viladrau, Osona, Spain; died 10 February 2004) was a Catalan physician and epidemiologist.

Casals' major legacies include his work on viral taxonomy, especially for insect-borne viruses, and significant ...

, Sonja Buckley

Sonja Buckley (June 13, 1918 – February 2, 2005) was a Swiss-born virologist. She was the first person to culture Lassa virus, the causative agent of Lassa fever, a potentially deadly disease that originated in Africa.

Biography

Sonja Gr ...

, and others. Casals contracted the fever, and nearly lost his life; one technician died from it. By 1972, the multimammate rat, ''Mastomys natalensis

The Natal multimammate mouse (''Mastomys natalensis'') is a species of rodent in the family Muridae. It is also known as the Natal multimammate rat, the common African rat, or the African soft-furred mouse. The Natal multimammate rat is the natu ...

,'' was found to be the main reservoir of the virus in West Africa, able to shed virus in its urine and feces without exhibiting visible symptoms.

Virology

Structure and genome

Lassa viruses are enveloped, single-stranded, bisegmented,

Lassa viruses are enveloped, single-stranded, bisegmented, ambisense

In molecular biology and genetics, the sense of a nucleic acid molecule, particularly of a strand of DNA or RNA, refers to the nature of the roles of the strand and its complement in specifying a sequence of amino acids. Depending on the context ...

RNA virus

An RNA virus is a virusother than a retrovirusthat has ribonucleic acid (RNA) as its genetic material. The nucleic acid is usually single-stranded RNA ( ssRNA) but it may be double-stranded (dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruses ...

es. Their genome is contained in two RNA segments that code for two proteins each, one in each sense, for a total of four viral proteins.

The large segment encodes a small zinc finger

A zinc finger is a small protein structural motif that is characterized by the coordination of one or more zinc ions (Zn2+) in order to stabilize the fold. It was originally coined to describe the finger-like appearance of a hypothesized struct ...

protein (Z) that regulates transcription and replication,

and the RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

(L). The small segment encodes the nucleoprotein

Nucleoproteins are proteins conjugated with nucleic acids (either DNA or RNA). Typical nucleoproteins include ribosomes, nucleosomes and viral nucleocapsid proteins.

Structures

Nucleoproteins tend to be positively charged, facilitating int ...

(NP) and the surface glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

precursor (GP, also known as the ''viral spike''), which is proteolytically cleaved into the envelope glycoproteins GP1 and GP2 that bind to the alpha-dystroglycan receptor and mediate host cell entry.

Lassa fever causes hemorrhagic fever frequently shown by immunosuppression. ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' replicates very rapidly, and demonstrates temporal control in replication. The first replication step is transcription of mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

copies of the negative- or minus-sense genome. This ensures an adequate supply of viral proteins for subsequent steps of replication, as the NP and L proteins are translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

from the mRNA. The positive- or plus-sense genome, then makes viral complementary RNA (vcRNA) copies of itself. The RNA copies are a template for producing negative-sense progeny, but mRNA is also synthesized from it. The mRNA synthesized from vcRNA are translated to make the GP and Z proteins. This temporal control allows the spike proteins to be produced last, and therefore, delay recognition by the host immune system.

Nucleotide studies of the genome have shown that Lassa has four lineages: three found in Nigeria and the fourth in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. The Nigerian strains seem likely to have been ancestral to the others but additional work is required to confirm this.

Receptors

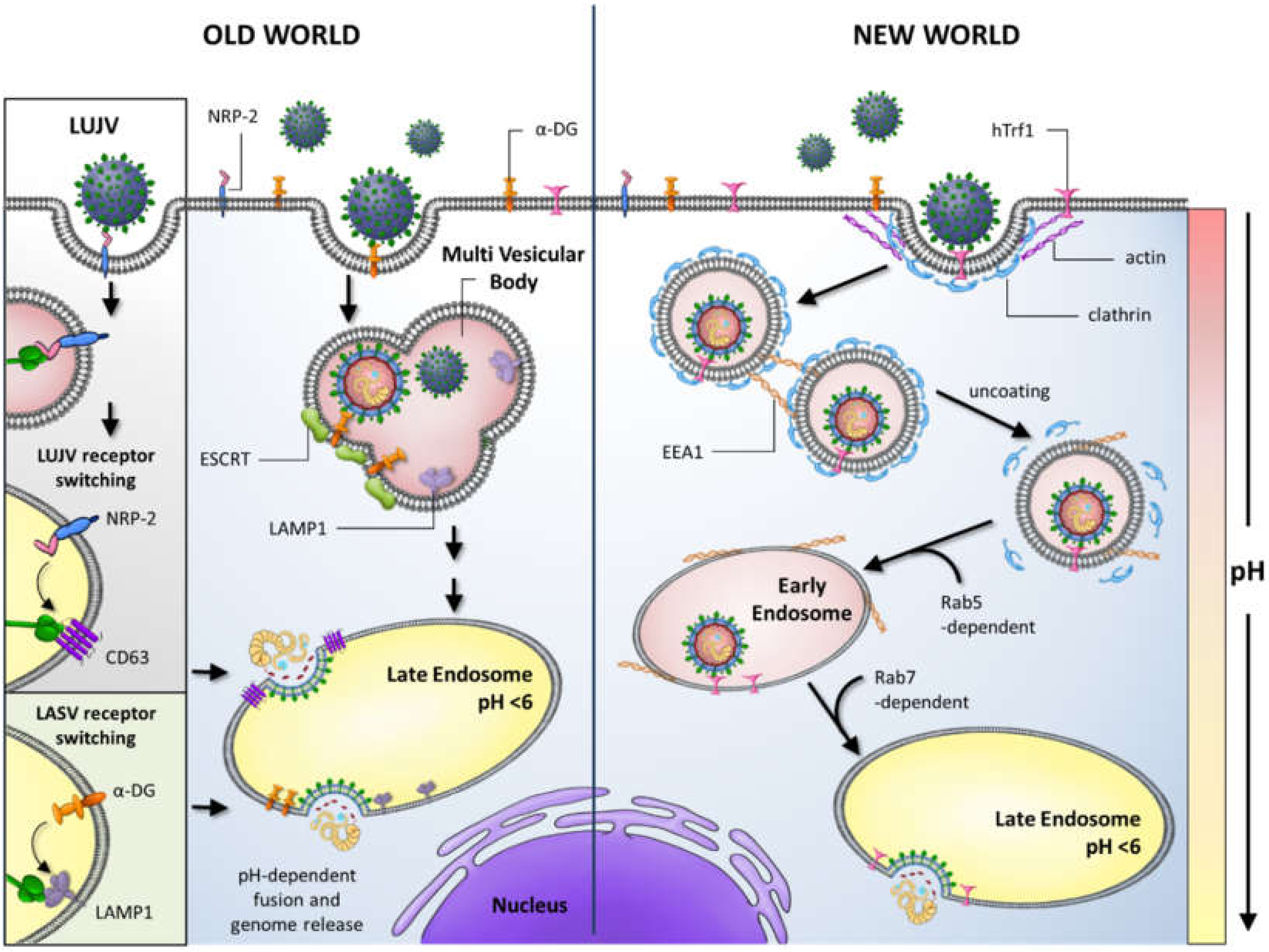

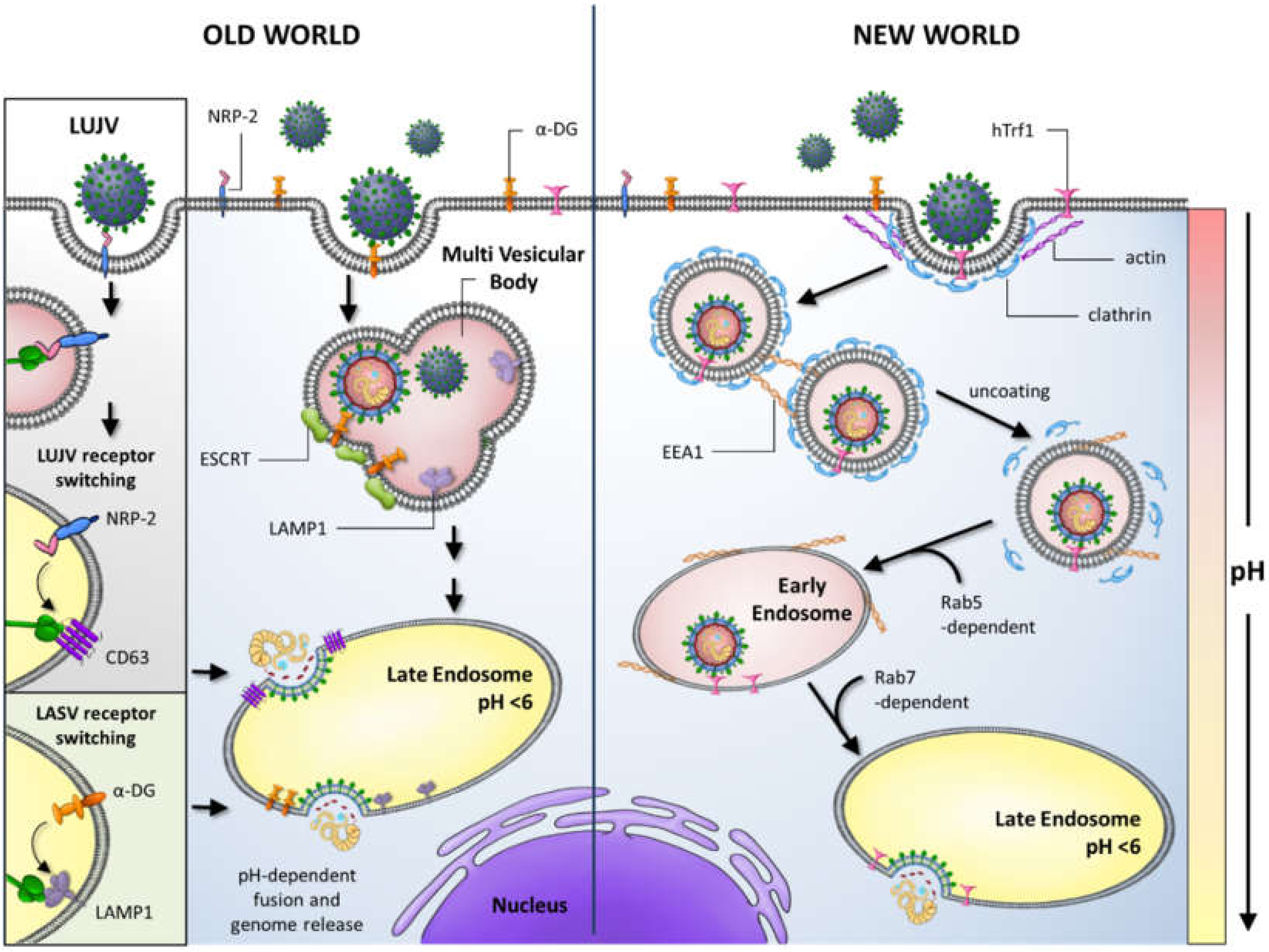

''Lassa mammarenavirus'' gains entry into the host cell by means of the cell-surface receptor the alpha-dystroglycan (alpha-DG), a versatile receptor for proteins of the

''Lassa mammarenavirus'' gains entry into the host cell by means of the cell-surface receptor the alpha-dystroglycan (alpha-DG), a versatile receptor for proteins of the extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix, is a three-dimensional network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide stru ...

. It shares this receptor with the prototypic Old World arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCM) is a rodent-borne viral infectious disease that presents as aseptic meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis. Its causative agent is ''lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus'' (LCMV), a member of the ...

. Receptor recognition depends on a specific sugar modification of alpha-dystroglycan by a group of glycosyltransferase

Glycosyltransferases (GTFs, Gtfs) are enzymes ( EC 2.4) that establish natural glycosidic linkages. They catalyze the transfer of saccharide moieties from an activated nucleotide sugar (also known as the "glycosyl donor") to a nucleophilic glycos ...

s known as the LARGE proteins. Specific variants of the genes encoding these proteins appear to be under positive selection in West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Maurit ...

where Lassa is endemic. Alpha-dystroglycan is also used as a receptor by viruses of the New World clade C arenaviruses (Oliveros and Latino viruses). In contrast, the New World arenaviruses of clades A and B, which include the important viruses Machupo

Bolivian hemorrhagic fever (BHF), also known as black typhus or Ordog Fever, is a hemorrhagic fever and zoonotic infectious disease originating in Bolivia after infection by ''Machupo mammarenavirus''.Public Health Agency of Canada: ''Machupo Vir ...

, Guanarito, Junin, and Sabia in addition to the non pathogenic Amapari virus, use the transferrin receptor 1

Transferrin receptor protein 1 (TfR1), also known as Cluster of Differentiation 71 (CD71), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TFRC'' gene. TfR1 is required for iron import from transferrin into cells by endocytosis.

Structure and func ...

. A small aliphatic amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

at the GP1 glycoprotein amino acid position 260 is required for high-affinity binding to alpha-DG. In addition, GP1 amino acid position 259 also appears to be important, since all arenaviruses showing high-affinity alpha-DG binding possess a bulky aromatic amino acid (tyrosine or phenylalanine) at this position.

Unlike most enveloped viruses which use clathrin

Clathrin is a protein that plays a major role in the formation of coated vesicles. Clathrin was first isolated and named by Barbara Pearse in 1976. It forms a triskelion shape composed of three clathrin heavy chains and three light chains. Whe ...

coated pits for cellular entry and bind to their receptors in a pH dependent fashion, Lassa and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus instead use an endocytotic pathway independent of clathrin, caveolin, dynamin

Dynamin is a GTPase responsible for endocytosis in the eukaryotic cell. Dynamin is part of the "dynamin superfamily", which includes classical dynamins, dynamin-like proteins, Mx proteins, OPA1, mitofusins, and GBPs. Members of the dynamin fa ...

and actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of over ...

. Once within the cell the viruses are rapidly delivered to endosome

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membrane can ...

s via vesicular trafficking albeit one that is largely independent of the small GTPase

GTPases are a large family of hydrolase enzymes that bind to the nucleotide guanosine triphosphate (GTP) and hydrolyze it to guanosine diphosphate (GDP). The GTP binding and hydrolysis takes place in the highly conserved P-loop "G domain", a pro ...

s Rab5 and Rab7

Ras-related protein Rab-7a is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''RAB7A'' gene.

Ras-related protein Rab-7a is involved in endocytosis, which is a process that brings substances into a cell. The process of endocytosis works by folding the ...

. On contact with the endosome pH-dependent membrane fusion occurs mediated by the envelope glycoprotein, which at the lower pH of the endosome binds the lysosome protein LAMP1

Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1) also known as lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1 and CD107a (Cluster of Differentiation 107a), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''LAMP1'' gene. The human ''LAMP1'' gene is locat ...

which results in membrane fusion and escape from the endosome.

Life cycle

The life cycle of ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is similar to the Old World arenaviruses. ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' enters the cell by the

The life cycle of ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is similar to the Old World arenaviruses. ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' enters the cell by the receptor-mediated endocytosis

Receptor-mediated endocytosis (RME), also called clathrin-mediated endocytosis, is a process by which cells absorb metabolites, hormones, proteins – and in some cases viruses – by the inward budding of the plasma membrane (invagination). Thi ...

. Which endocytotic pathway is used is not known yet, but at least the cellular entry is sensitive to cholesterol depletion. It was reported that virus internalization is limited upon cholesterol depletion. The receptor used for cell entry is alpha-dystroglycan

Dystroglycan is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''DAG1'' gene.

Dystroglycan is one of the dystrophin-associated glycoproteins, which is encoded by a 5.5 kb transcript in ''Homo sapiens'' on chromosome 3. There are two exons that are s ...

, a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed cell surface receptor for extracellular matrix proteins. Dystroglycan, which is later cleaved into alpha-dystroglycan and beta-dystroglycan is originally expressed in most cells to mature tissues, and it provides molecular link between the ECM and the actin-based cytoskeleton. After the virus enters the cell by alpha-dystroglycan mediated endocytosis, the low-pH environment triggers pH-dependent membrane fusion and releases RNP (viral ribonucleoprotein) complex into the cytoplasm. Viral RNA is unpacked, and replication and transcription initiate in the cytoplasm. As replication starts, both S and L RNA genomes synthesize the antigenomic S and L RNAs, and from the antigenomic RNAs, genomic S and L RNA are synthesized. Both genomic and antigenomic RNAs are needed for transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

and translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

. The S RNA encodes GP and NP (viral nucleocapsid protein) proteins, while L RNA encodes Z and L proteins. The L protein most likely represents the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. When the cell is infected by the virus, L polymerase is associated with the viral RNP and initiates the transcription of the genomic RNA. The 5’ and 3’ terminal 19 nt viral promoter regions of both RNA segments are necessary for recognition and binding of the viral polymerase

A polymerase is an enzyme ( EC 2.7.7.6/7/19/48/49) that synthesizes long chains of polymers or nucleic acids. DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase are used to assemble DNA and RNA molecules, respectively, by copying a DNA template strand using base- ...

. The primary transcription first transcribes mRNAs

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

from the genomic S and L RNAs, which code NP and L proteins, respectively. Transcription terminates at the stem-loop (SL) structure within the intergenomic region. Arenaviruses use a cap snatching

The first step of transcription for some negative, single-stranded RNA viruses is cap snatching, in which the first 10 to 20 residues of a host cell RNA are removed (snatched) and used as the 5′ cap and primer to initiate the synthesis of the na ...

strategy to gain the cap structures from the cellular mRNAs, and it is mediated by the endonuclease

Endonucleases are enzymes that cleave the phosphodiester bond within a polynucleotide chain. Some, such as deoxyribonuclease I, cut DNA relatively nonspecifically (without regard to sequence), while many, typically called restriction endonucleases ...

activity of the L polymerase and the cap binding activity of NP. Antigenomic RNA transcribes viral genes GPC and Z, encoded in genomic orientation, from S and L segments respectively. The antigenomic RNA also serves as the template for the replication. After translation of GPC, it is posttranslationally modified in the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

. GPC is cleaved into GP1 and GP2 at the later stage of the secretory pathway. It has been reported that the cellular protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the ...

SKI-1/S1P is responsible for this cleavage. The cleaved glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

s are incorporated into the virion

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

envelope when the virus buds and release from the cell membrane.

Pathogenesis

Lassa fever

Lassa fever, also known as Lassa hemorrhagic fever (LHF), is a type of viral hemorrhagic fever caused by the Lassa virus. Many of those infected by the virus do not develop symptoms. When symptoms occur they typically include fever, weakness, h ...

is caused by the ''Lassa mammarenavirus''. The symptoms include flu-like illness characterized by fever, general weakness, cough, sore throat, headache, and gastrointestinal manifestations. Hemorrhagic manifestations include vascular permeability.

Upon entry, the ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' infects almost every tissue in the human body. It starts with the mucosa

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is ...

, intestine, lungs and urinary system, and then progresses to the vascular system.

The main targets of the virus are antigen-presenting cell

An antigen-presenting cell (APC) or accessory cell is a cell that displays antigen bound by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on its surface; this process is known as antigen presentation. T cells may recognize these complexes using ...

s, mainly dendritic cell

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (also known as ''accessory cells'') of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system. ...

s and endothelial cells.

In 2012 it was reported how ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' nucleoprotein (NP) sabotages the host's innate immune system

The innate, or nonspecific, immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies (the other being the adaptive immune system) in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an older evolutionary defense strategy, relatively speaking, and is the ...

response. Generally, when a pathogen enters into a host, innate defense system recognizes the pathogen-associated molecular pattern

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are small molecular motifs conserved within a class of microbes. They are recognized by toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in both plants and animals. A vast arra ...

s (PAMP) and activates an immune response. One of the mechanisms detects double stranded RNA (dsRNA), which is only synthesized by negative-sense viruses. In the cytoplasm, dsRNA receptors, such as RIG-I

RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene I) is a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor (PRR) responsible for the type-1 interferon (IFN1) response. RIG-I is an essential molecule in the innate immune system for recognizing cells that have been infect ...

(retinoic acid-inducible gene I) and MDA-5 (melanoma differentiation associated gene 5), detect dsRNAs and initiate signaling pathways

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events, most commonly protein phosphorylation catalyzed by protein kinases, which ultimately results in a cellula ...

that translocate IRF-3

Interferon regulatory factor 3, also known as IRF3, is an interferon regulatory factor.

Function

IRF3 is a member of the interferon regulatory transcription factor (IRF) family. IRF3 was originally discovered as a homolog of IRF1 and IRF2. IR ...

(interferon

Interferons (IFNs, ) are a group of signaling proteins made and released by host cells in response to the presence of several viruses. In a typical scenario, a virus-infected cell will release interferons causing nearby cells to heighten the ...

regulatory factor 3) and other transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fu ...

s to the nucleus. Translocated transcription factors activate expression of interferons 𝛂 and 𝛃, and these initiate adaptive immunity

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system ...

. NP encoded in ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is essential in viral replication

Viral replication is the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. Through the generation of abundant copies of its genome an ...

and transcription, but it also suppresses host innate IFN response by inhibiting translocation of IRF-3. NP of ''Lassa mammarenavirus'' is reported to have an exonuclease

Exonucleases are enzymes that work by cleaving nucleotides one at a time from the end (exo) of a polynucleotide chain. A hydrolyzing reaction that breaks phosphodiester bonds at either the 3′ or the 5′ end occurs. Its close relative is the ...

activity to only dsRNAs. the NP dsRNA exonuclease activity counteracts IFN responses by digesting the PAMPs thus allowing the virus to evade host immune responses.

See also

*Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) is a foundation that takes donations from public, private, philanthropic, and civil society organisations, to finance independent research projects to develop vaccines against emerging ...

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q24719561, from2=Q1806636 Animal viral diseases Biological weapons Arenaviridae Tropical diseases Zoonoses